Movies

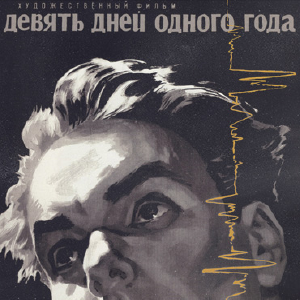

Films are embedded within the cultural values of the society in which they are created. During the Cold War, films not only reflected the conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, but also shaped how the mass audiences and political actors in both of these states understood the conflict. We should be careful to not simply label the films produced during this period as “propaganda.” The line between propaganda and art can be deceptively thin. Mikhail Romm, who directed two of the most virulently anti-American films, The Russian Question (1948) and The Secret Mission (1950), also directed one of the most complex and potentially subversive films of the decade in Soviet cinema: Nine Days in One Year (1962).

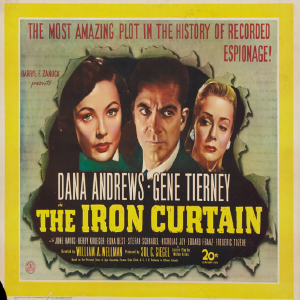

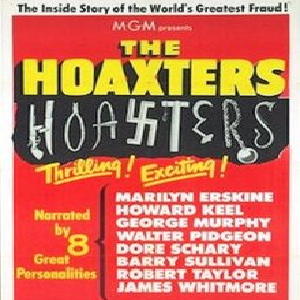

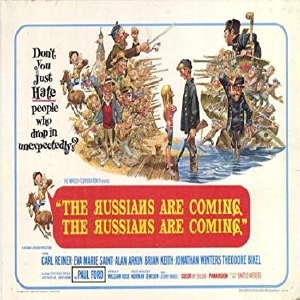

From 1945 to the mid-1950s both Soviet and American film productions about the Cold War tried to demonize their political and ideological rivals. Films such as The Russian Question (1948), Meeting on the Elbe (1949), and The Secret Mission (1950) all condemn American elites as imperialistic and hungering for war with the Soviet Union, while also showing America as connected to the recently defeated fascist enemy, Nazi Germany. Interestingly, in each of these films a distinction is made between the American people and the American elites, and it is consistently emphasized that the American elites are the enemy not the American people. On the other hand, American films such as The Iron Curtain (1948) and The Hoaxters (1952) dramatized the danger of a communist “fifth column” inside America. The Hoaxsters also directly compares the Soviet Union to Nazi Germany arguing that there is no real difference between their governing strategies.

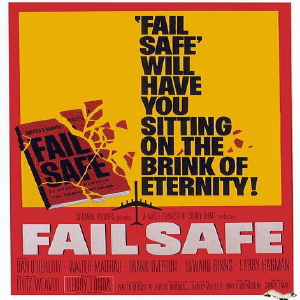

In the 1960s, films in both states reflected growing fear of the unintended drawbacks of nuclear power and its potential for causing nuclear armageddon. This is shown in the Soviet film Nine Days in One Year (1962) and more directly in the American films Fail-Safe (1964) and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

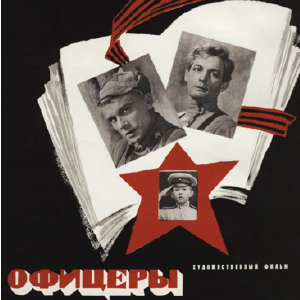

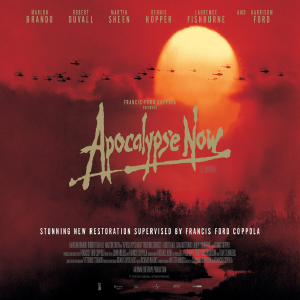

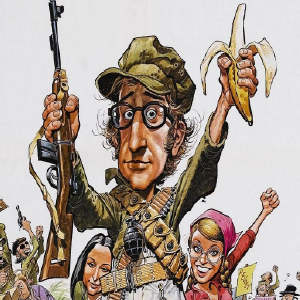

During the 1970s, due in part to détente, Cold War rhetoric in films calmed down, but was still present indirectly. Films like Neutral Waters (1968), Officers (1971), and the Liberation movie series (1970 – 1971) all glorified the Soviet Union’s military. Meanwhile in America, Woody Allen’s Bananas (1971) took a critical and comedic look at the Cold War, and eight years later Francis Ford Coppola took an equally critical, though less comedic, look at the Vietnam War and America’s resulting trauma’s from it in his monumental Apocalypse Now (1979). One could argue that in this decade, cultural conservatism, shown through the veneration of the military in the Soviet films continued to reign supreme or even increase, while at the same time liberalism and more critical examinations of the Cold War and America’s military ventures grew in the United States.

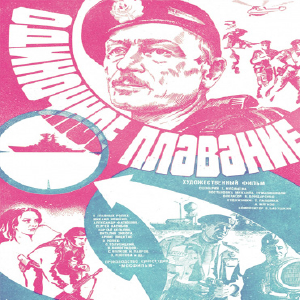

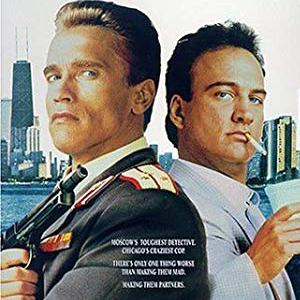

In the early 1980s, fueled in part by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the election of Ronald Regan in 1980, Cold War rhetoric became increasingly aggressive, violent, and direct in both American and Soviet films. Both cinemas created action-adventure films in which the opposing state was the enemy. Emblematic in this regard are the American film Red Dawn (1984) and the Soviet film Solo Voyage (1985).